Craig Claiborne, who was born in 1920, took until he was nearly 40 to find himself. Born in Mississippi, he came of age just as the US was entering World War II, and served in the Navy in North Africa, Sicily, and the Pacific. After the war Claiborne moved first to Chicago, to work in public relations, and then to Paris, where he stayed until his money ran out. It was in Chicago that he learned to cook, and in Paris that he learned to eat. More specifically, on the trip home on the Ile de France, he ate “the dish that changed his life,” turbotin à l’infante. When the Korean War broke out, Claiborne went back on active duty, then spent a year in the Marshall Islands. While there, he formed the ambition to write about food for the New York Times.

He was not an untutored naif. His mother had run a boarding house in Mississippi that was famous for its table; his sister had given him a copy of ‘The Joy of Cooking’ and he learned to cook with that book. (I have my grandmother’s 1953 edition. It’s a wonderful book.) And he made sure to train himself: in the early 1950s Claiborne attended the Professional School of the Swiss Hotel Keepers Association in Lausanne (now the Lausanne Hotel School) where he was trained in cuisine, service, and management in a demanding course that was half in the classroom, half in field placements. So Claiborne knew food and, critically, he knew service. He also knew he wanted to write (he had attended the journalism school at the University of Missouri). After graduating, he hit the sidewalks of New York.

In McNamee’s telling Claiborne single-handedly created the American food scene. His output, from his early pieces, brief reports in Gourmet, was prodigious. He didn’t just write about fancy French food, he opened himself up to the cuisines immigrants brought with them in steerage,: Italian pastas, cheeses, and pastries, Asian cooking, and Latin American dishes. (Claiborne also maintained himself with cooking demonstrations at Bloomingdale’s.) And then he talked his way into the job of food editor at the New York Times. He made a big splash in 1959 with a front-page article about the decline of service and food in the great American restaurants. He began a lifelong friendship, and collaboration, with Pierre Franey. He provided what McNamee describes as ‘generous support’ to “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” by Simone Beck, Louisette Bertholle, and Julia Child. He gave, and attended, sumptuous parties — McNamee devotes a chapter to a Gardiner’s Island picnic that was staffed by famous chefs and covered by Life Magazine — and attracted national attention.

As his public life was becoming more and more successful, Claiborne did not lack the means to a happy private life. He had a house near Pierre Franey’s, and spent a lot of time with Franey, his wife, and their children. Other close friends came and went. But it was not an easy time to be a gay man, and Claiborne was never able to develop a lasting personal relationship. As McNamee puts it, Claiborne described himself, “‘As much as I possibly could be, I was gloriously happy’ . . . that closely hedged caution was pure Craig Claiborne.’” Claiborne had a history of cutting people, including his mother, off (he refused to attend her funeral). McNamee quotes Claiborne: “I learned to shed ties, more often than not with hideous effect, but without retreat or apology.” Throughout all the years of success Claiborne drank, and drank, and drank, with perhaps predictable health consequences in his final decade. He also had (at least) two drunk driving arrests and was ultimately forced to retire from the Times.

Like any life, Claiborne’s had its glorious moments, and some deeply sad ones. The glorious ones were also pretty glamorous, and will be particularly resonant for anyone interested in food or who is familiar with some or all of the many cookbooks Claiborne published. The sad ones will seem all too familiar. McNamee suggests that the disappointments in his personal life caused Claiborne’s alcoholism, though perhaps he has reversed the causality. I found the book to be more of a celebration than a dirge, though others have not. What do you think? Let us know in the comments.

Have a book you want me to know about? Email me at asbowie@gmail.com. I also blog about metrics for people who hate numbers here.

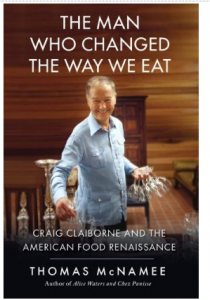

- Photo via Amazon.com.