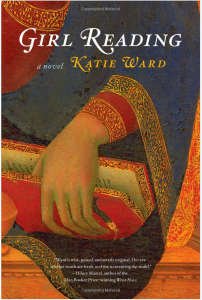

We forget, often, that artifacts survive us, but survive they do, and that is one of the points that Katie Ward makes in her fascinating new novel, “Girl Reading.” Each chapter is about a work of art, usually but not always a painting, always involving a woman and a book. Who are the women in the pictures? What brought them to the artist’s attention? Starting with the work of art, and some known facts about the artist’s life, Ward imagines a story that results in the work’s creation. The book starts in the 14th century with Simone Martini’s Annunciation, and runs until 2060 with an ‘enmeshed,’ that is to say digital, image of a Sibil.

We forget, often, that artifacts survive us, but survive they do, and that is one of the points that Katie Ward makes in her fascinating new novel, “Girl Reading.” Each chapter is about a work of art, usually but not always a painting, always involving a woman and a book. Who are the women in the pictures? What brought them to the artist’s attention? Starting with the work of art, and some known facts about the artist’s life, Ward imagines a story that results in the work’s creation. The book starts in the 14th century with Simone Martini’s Annunciation, and runs until 2060 with an ‘enmeshed,’ that is to say digital, image of a Sibil.

After 14th century Italy, the book moves to 16th century Netherlands (where the painter has a memory of a painting he saw as a student in Italy) and then on to 17th century England. Thereafter the book remains in the United Kingdom. The stories vary in quality. The 14th, 17th, and 18th century stories are labored and distant. I’m not sure why – perhaps the author’s believes that these works of art are less accessible to the modern viewer? (I personally disagree, particularly about the Dutch painter Pieter Janssens Elinga. Or those other wondrous painters of Dutch interiors, Vermeer and Saenredam.) Or maybe they were less accessible to her? The novel comes alive in the 19th century, when it contrasts a pair of twins, one a photographer and the other a medium. From then on, the stories become consistently better.

The stories are linked thematically, rather than through character. There’s also a more literal link, as an object, or the thought or memory of an object, from the previous story turns up in its successor. It’s an original and imaginative approach, both to the works of art and to the stories. At the same time, I needed to see the pictures to understand the story, so I looked them up online. I have pinned pictures of as many of the works of art Ward mentions in her text and a note at the end (perhaps underlining the point of her final story, which explores the loss when all we see are images in the web instead of the physical object) on a Pinterest board. (Pinterest is free but you have to join; you can use your Facebook or Twitter account.)

One feature of the writing increased the emotional distance throughout the work: Ward joined a modern trend and did not include quotation marks, leaving it to the reader to decide what is spoken, and what is interior. I can see how, used sparingly, this technique can have an impact; but used throughout a book, as in this case, it’s off-putting. I’m not the only person who feels this way about quotation marks; here’s the author Lionel Shriver on the issue.

Towards the end of the book, Ward has one of her characters say (or so the context suggests anyway), “Sibil makes you experience, in mesh real or fictionalized aspects of what is already there embedded within a real-world object.” For the character, as for Ward, the work of art is a starting point. Ward, like her artist, shows us the work in a new way. Do you agree? Let us know in the comments.

Have a book you want me to know about? Email me at asbowie@gmail.com. I also blog about metrics for people who hate numbers here.

Photo source: Amazon.com