“The simplest description of emptiness in the Buddhist teachings is this sentence: This is because that is. A flower cannot exist by itself alone. To be can only mean to inter-be. To be by oneself alone is impossible. Everything else is present in the flower; the only thing the flower is empty of is itself.”

— Thich Nhat Hanh

Where do we find the origin of the profoundly original?

Earlier this week a Kraftwerk Symposium took place in Birmingham, England, and frankly, THAT’S FANTASTIC. Kraftwerk are INARGUABLY the second most influential band of the past half century, and a concentrated academic examination of their work is not only long overdue, it makes me happier than a peanut butter cup wrapped inside a larger peanut butter cup. I wasn’t able to make it to the symposium because I had a previous commitment to, uh, have a life (not to mention that my time is consumed pressuring the International Court at The Hague to charge Dick Van Dyke with Crimes Against Humanity for his English accent in Mary Poppins).

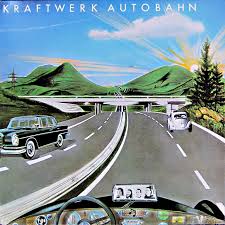

Now, Kraftwerk are not my favorite band – they’re not even my favorite krautrock band – but that has nothing to do with their importance. In 1973 and ’74 (on their 3rd LP, Ralf und Florian and coming to fruition on the legitimately historic Autobahn album), Kraftwerk replaced all elements of the pop/rock rhythm section with a pulsing, throbbing, quantized synth; in other words, they replaced the drums and the bass, without exception, with simple yet satisfying synth burps and nothing but simple yet satisfying synth burps. Make no mistake: although other artists had experimented with using the synth as a defacto drum or bass supplement or substitute (for instance, the Beach Boys on “Do It Again,” even the original Doctor Who Theme, remarkably devised by Ron Grainer and Delia Derbyshire in 1963), no artist had said this is our sound; this our body and our soul, and we now challenge you to accept that a complete pop music rhythm section can be created by the quantized synthesizer.

Now, Kraftwerk are not my favorite band – they’re not even my favorite krautrock band – but that has nothing to do with their importance. In 1973 and ’74 (on their 3rd LP, Ralf und Florian and coming to fruition on the legitimately historic Autobahn album), Kraftwerk replaced all elements of the pop/rock rhythm section with a pulsing, throbbing, quantized synth; in other words, they replaced the drums and the bass, without exception, with simple yet satisfying synth burps and nothing but simple yet satisfying synth burps. Make no mistake: although other artists had experimented with using the synth as a defacto drum or bass supplement or substitute (for instance, the Beach Boys on “Do It Again,” even the original Doctor Who Theme, remarkably devised by Ron Grainer and Delia Derbyshire in 1963), no artist had said this is our sound; this our body and our soul, and we now challenge you to accept that a complete pop music rhythm section can be created by the quantized synthesizer.

Every synthetically thumping rhythm section you have heard since then – from the obvious Kraftwerk homages like “Funkytown” and Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock” to the ubiquity of the modern tsk-and-burp/boots’n’pants beat in virtually all modern pop and dance music – can be traced, without fail, to Kraftwerk’s amazing invention. NO other moment in pop is as absolute and viscerally fundamental as “Autobahn.” I’ll be honest: I am a fairly avid student of this shit, and I am hard-pressed to find a moment in post-World War II mainstream pop history that is as absolutely new and defining. There have been plenty of other remarkable scene changes in the last 70 years (Hardrock Gunter and Ike Turner’s use of distorted electric guitar in r’n’b and hillbilly music in 1950 and ‘51; Bo Diddley replacing the old pick and slap of hillbilly rock with fat ham slabs of rhythm roar half a decade later; Dave Davies invention of the modern bar chord riff in 1964; the Ramones massive, massively original, and massively glorious reduction of all existing rock memes in ’74; and so on), but Kraftwerk’s invention of the totally self-contained synth-generated rhythm section is likely the biggest purely musical scene change in the history of rock/pop. I mean, the Fabs are, no doubt, the most influential band of all time, but Kraftwerk are a very, very close second, and very likely number one if you drop long held generational prejudices against dance music.

Having said that…one must acknowledge that the basic roux that flavored Kraftwerks’ gumbo had to come from somewhere (please re-read the quote that begins this piece – only a fool or a fundamentalist Christian believes in Virgin birth). Now, the foundation of the Kraftwerk sound was a pulsing, metronomic beat that mesmerized with a steady tick and minimal chord changes. Keep that in mind. Perusing the program for the symposium, I’m not sure this point was actually addressed:

Circa 1971, after their release of their peculiar, anti-jazz, anti-pop, bongo-and-flutey first album, Kraftwerk briefly had a three-piece line-up, comprised of Florian Schneider (flute and synths), Klaus Dinger (drums), and Michael Rother (guitar). Video and audio of this short-lived line-up reveal a band playing intense, punching, pulsing jams with minimal chord changes, resembling precise mongoloids playing “Sister Ray,” or perhaps you could say they sound like some stoned, happy, and aggressive Germans trying to blend Stooges/Hendrix shrrrroarrr-wang-wang with the mono-chord jams of early NYC minimalist composers like LaMonte Young and Tony Conrad. The music of Schneider, Dinger, and Rother is vastly original – it reduces the idea of “jam” to John Cale drones married to a caveman surf beat. This sound reached it’s fullest fruition when Dinger and Rother split off to form Neu!, a band whose phased, ticking, rumbling, endless one-chord explorations made for some of the most original, powerful, and influential rock ever recorded.

(the Incredible Schneider/Dinger/Rother Kraftwerk, late 1971)

But Neu! wasn’t the only child of the brief and brilliant Schneider/Dinger/Rother Kraftwerk. The future, commercially giant Kraftwerk was Neu!’s remarkable twin. It is clear – very goddamn clear – that when Schneider reunited with Ralf Hutter (who returned to the band he co-formed in 1972), there was a conscious decision to leave the odd, dumbed-down proggy thumps, bells, and whistles behind (again, the early Kraftwerk sound resembles a very stoned, very, minimalist free jazz group doing collegiate exercise in interpreting Stockhausen), and instead attempt a sound that IMITATED Dinger and Rother’s ultra-minimal motorway beat (the actual name is “motorik”) that hinted at long highways, minimal variation, and maximum energy.

So I posit – shit, I barely need to posit it, there’s plenty of evidence to back it up – that the “Autobahn” sound that reinvented pop was “just” an attempt to replicate on synths the sound that Dinger/Rother had brought to Kraftwerk during their brief time in the band. Now, NONE of that is to minimize the invention; and there is great, ENORMOUS, radical genius in Hutter and Schneider’s decision to reinterpret Dinger and Rother’s motorway drive with synths and synths alone – but I am anxious to give credit where credit is due. I will add, for the sake of accuracy/completion, that an academic-type could make a fairly strong case for the sound of the Schneider/Dinger/Rother Kraftwerk being a more simplistic, driving, spacious exploration of the herky-jerky seizure-on-the-railway sound that the Schneider/Hutter/Dinger Kraftwerk had explored on a first-album track called “Ruckzuck” – remember, “Everything else is present in the flower”.

Now back to those emails to the International Court at The Hague.