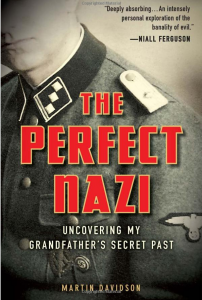

Many of the books about the Holocaust that have recently found their way to this household have described what happened to particular families after 1939 (“After Long Silence” by Helen Fremont), or about searches made long after the war to discover what happened to one’s family (“The Lost” by Daniel Mendelsohn, “Walking Since Daybreak” by Modris Eksteins). I highly recommend all three of those books. And now I’m adding another to the list, “The Perfect Nazi” by Martin Davidson.

Many of the books about the Holocaust that have recently found their way to this household have described what happened to particular families after 1939 (“After Long Silence” by Helen Fremont), or about searches made long after the war to discover what happened to one’s family (“The Lost” by Daniel Mendelsohn, “Walking Since Daybreak” by Modris Eksteins). I highly recommend all three of those books. And now I’m adding another to the list, “The Perfect Nazi” by Martin Davidson.

Like Fremont’s and Mendelsohn’s books, Davidson’s memoir traces what befell his family during the Second World War. As is obvious from the title, however, Davidson’s family wasn’t lost. His father was Scots, his mother German. And what was lost, or buried, or perhaps just ignored, as Davidson describes it, was his German grandfather’s history as a Nazi.

It’s not as if Davidson and his sister, who accompanied him on his quest, didn’t wonder. They went on summer holidays to visit their grandparents (who had separated after the war) in Berlin. There were other family members, too, “family traces, the names of people whom, though they were still alive, we never met.” These included a great-uncle, a great-grandmother, and a step-great-grandfather. It was as if there were a shared family will not to discuss what happened.

Their grandfather, Bruno Langbehn, liked to cause trouble in the family, taking the adolescent Davidson and his sister out for dinner, then plying them with alcohol and bringing them home drunk. He talked a little, about his favorite leisure activity, the apparently benign act of “meeting his Kriegskameraden (his wartime buddies) around a regular Stammtisch, the table that many German pubs have, reserved for use” by regular customers. And, once he died, Davidson’s mother started to let out the tale: her father had not been in the regular army. He’d been in the SS.

So, using archives and records, interviewing family members and relying on histories, Davidson traces his grandfather’s progression. Langbehn’s fascist activities started early; he joined the Nazi Party in 1926, at the age of 19. His low membership number of 36,931 stood him in good stead later, after the Nazi Party had taken power. In the 1920s it made him an outlier. That year, he joined the Nazi paramilitary force the SA, the brownshirts. He was among the throngs who marched at the Nuremberg rallies, and fought in the streets. After brutal, violent marches, he would repair with the members of his Sturm to the local pub, where they would drink and sing, celebrating the violence they had inflicted. In 1937, he applied to and was accepted by the SS. He was injured during the fight for France early in the war. He ended the war years in Prague, working for the SS.

Langbehn was trained as a dentist, and was not a particularly competent or organized monger of SS cruelty. He was, in Davidson’s words, “ a compulsive joiner, a man at his happiest inside institutions, a natural committee member.” And that’s what makes the story so harrowing. As Davidson describes his grandfather’s war years, the ease with which any German could become enraptured by, and convinced of, Hitler’s horrid vision emerges from his factual, historical discussions. Davidson is careful not to speculate about what his grandfather’s state of mind might have been at any point in this trajectory, letting Langbehn’s actions speak, which they do, quite clearly. This can’t have been an easy book to research, or write. It is one that everyone should read.

Have a book you want me to know about? Email me at asbowie@gmail.com. I also blog about metrics for people who hate numbers here.