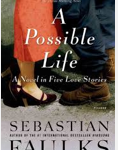

Sebastian Faulks gives his new novel “A Possible Life” the subtitle “A Novel in Five Love Stories.” These are not ordinary love stories and, as you might expect with Faulks, they rarely end happily. In each, there’s a betrayal, sometimes more than one.

Sebastian Faulks gives his new novel “A Possible Life” the subtitle “A Novel in Five Love Stories.” These are not ordinary love stories and, as you might expect with Faulks, they rarely end happily. In each, there’s a betrayal, sometimes more than one.

Geoffrey Talbot finished university just before the Second World War broke out. After a year as a teacher he enlisted, but was not particularly successful as an officer. His mother is French, and his language skills allow him to transfer into a different branch – one in which he is infiltrated into France. He winds up in a concentration camp. One day he thoughtlessly answers a call for French speakers – and finds himself translating German orders to a trainload of just-arrived French Jews. He may or may not know where they are going, but he learns, quickly enough. It’s not his fault he’s there, he does everything he can to escape, but his culpability is not entirely thrust upon him.

That is true of the characters in the subsequent stories as well. The next, “Billy” starts in London in 1859 – when Billy’s parents must send him to the workhouse, sacrificing him so the rest of the family can survive. Billy makes something of himself from this unpromising beginning but he, too, has made choices that, though they seemed reasonable at the time, turn out, once 15 or 20 years have unfolded, to be utterly wrong. We can’t know the future, and Billy makes a good case for not necessarily knowing everything about the past, either.

All the themes are present in the final story, “Anya,” set in 1971. Unlike the other stories, it’s a first person narrative, told from the point of view of a young English musician, Jack. It’s also clear from the first page of the story that this one is set in the US (the others are all set in Europe). Jack is living in a farmhouse with his girlfriend, deciding what to do next, living off the royalties from a couple of records but not inclined to reunite with his band. Then Anya, a folk musician, enters his life. Jack produces her record, and then another, and goes on tour with her, entering an intense, sex, drug, and alcohol filled period – until Anya leaves.

Throughout, every character is morally compromised, and it’s often not entirely clear who is the betrayer and who the betrayed. Among the five stories, the moral complexity arises organically, accidentally, as in Geoffrey’s case, out of the innocent choices one makes every day. But every one of those choices can affect another, often in ways that we cannot foresee. At the very end of the book, Jack says:

“Sometimes my whole life seems like a dream; occasionally I think that someone else has lived it for me . . . So when eventually my hour comes and I go down in that darkness . . . there’ll be no need to mourn me or repine. Because I think we’re all in this thing, like it [or] not, forever.”

We are our stories, Faulks suggests, and they will go on. The interplay between what we have done and what the others around us have done makes these stories a compelling novel. Do you agree with Jack’s conclusion? Let us know in the comments.

Have a book you want me to know about? Email me at asbowie@gmail.com. I also blog about metrics at asbowie.blogspot.com.