Change is constant, change is unavoidable. All of our favorite buildings will one day be destroyed, all our favorite bars reduced to rubble or hipster coffee houses, all our treasured theatres where the rock bands of our youth stomped and swaggered, with sticky floors and soaring, chipped ceilings turned ash-gray by decades of smoke, will be reduced to dormitories or parking lots. We have lived long enough to have seen typewriters, analog television, the art of the phone call, the joy of cracking open the crease of a cardboard gatefold album sleeve, all vanish and disappear.

So what. Things change. You can never put your hand in the same river twice. Water is always moving. So what.

But I do find myself deeply sad that the age of Artisanal Recording is gone forever.

Now, I said sad, but not regretful. I’ll explain that shortly.

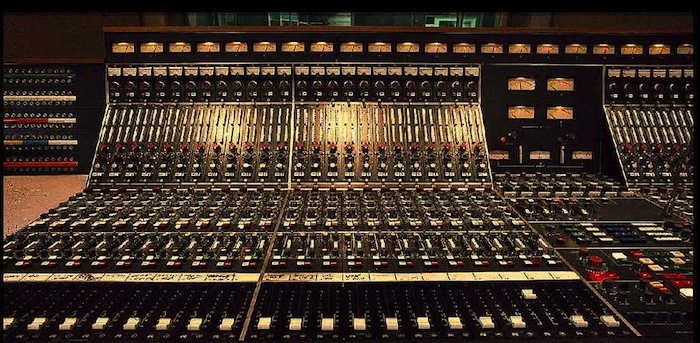

Prior to the ubiquity of computer-based recording technologies, records were made at massive console desks, with inputs feeding into giant, needy tape machines; This resulted in extraordinary achievements of patience, coordination, imagination, mystery, and happy accident; and whereas this process, time consuming and often frustrating, resulted in hundreds of thousands of magical recordings (from Louis Armstrong’s Hot 5 recordings to the Ramones, and so very many more), there are times when the process itself — that is, not just the act of a magical band being recorded, but the method itself being almost supernaturally inspired – resulted in Art, in Michelangelo’s David, in Brunelleschi’s Dome.

Now, let me state, very goddamn clearly, that generally I applaud this change. Personally, I think the onset of the computer recording era actually engenders and encourages imagination, spontaneity, and a more perfect path between artistic vision and result. Also, a good engineer, producer or imaginative musician can actually make trashier, noisier results on the computer; it is actually easier to make a “lo-fi” recording, reproducing the spirit of, say, the Sonics or the Monks or whoever, on a computer-based system than on a tape-based system.

When I speak of Artisanal Recording, I am not just talking about the Age of Tape. I am talking about a very specific mind-set and creative process: using the console, tape machines, human power, and instruments in extraordinary harmony to produce an extremely elaborate and holistic result. In other words, I am not just talking about using hammer and tools and a few cranes to put up an apartment building; I am talking about using hammer and tools and a few cranes to put up the Cathedral of Chartres, using (essentially) manual tools to create something so delicate, so reliant on every other element, so firm but light, and so elaborate that the absence of even one element could lead to collapse of the whole thing.

When I speak of Artisanal Recording, I am not just talking about the Age of Tape. I am talking about a very specific mind-set and creative process: using the console, tape machines, human power, and instruments in extraordinary harmony to produce an extremely elaborate and holistic result. In other words, I am not just talking about using hammer and tools and a few cranes to put up an apartment building; I am talking about using hammer and tools and a few cranes to put up the Cathedral of Chartres, using (essentially) manual tools to create something so delicate, so reliant on every other element, so firm but light, and so elaborate that the absence of even one element could lead to collapse of the whole thing.

When I speak of Artisanal Recording, you think I am going to cite Sgt. Pepper or Pet Sounds, yes?

No. In essence, those amazing works of art are “just” recordings of extraordinary performances, extraordinary arrangements. Artisanal Recording is the art of extreme coordination in the control room, with not just the instruments and arrangements being orchestrated perfectly (as is the case with Pepper/Sounds), but the coordination between those factors and the console desk and the tape machine being so precise as to be virtually – if not literally – at the level of the finest renaissance craftsmen.

When I consider the pinnacle of Artisanal Recordings, some wonderful records immediately spring to mind, especially the work of Queen and Abba. Both groups combined stunning songwriting and performance talent with incredible, artisanal work in the control room, making the consoles and the machines do the artists’ bidding through elaborate synchronization, invention, and creative insight. I have often thought that an instructor could teach an entire semester of a class on music production just by using “S.O.S.” by Abba. But one recording stands out as the pinnacle, the most gorgeous realization, of the lost age of Artisanal Recording.

And that’s “More Than A Feeling” by Boston.

I’m sure Boston could play “More Than A Feeling” perfectly well live, but that’s not what’s going on in the studio recording of that song. What’s happening here is an astonishing union of hands, technical elements, tape decks, mixing desks, to produce a unique product that is a precise blend of intent, imagination, patience, melody, energy, and emotional resonance.

First of all, the song fades in, which boldly and plainly announces it as a studio concoction; how many songs can you name that fade in? Probably, off the top of your head, just one — the Beatles’ “Eight Days A Week.” After the fade-in (often obscured on the radio), the first thing the listener is really aware of is a shimmering, attentive arpeggio, an immediately identifiable signature that tells us very little about what’s to come, but announces that something very important is going on here. The guitar sound on this arpeggio, like all the guitars in the song, are an expert mixture of multiple guitars – at least one acoustic and multiple electrics, and I suspect a balance of 12 strings and 6 strings – morphed into one seamless and unique whole.

RELATED: READ ALL TIM SOMMER’S COLUMNS

From here on, we encounter a rare balance of mathematical precision and evocative contact with listener; even though a casual listener would not necessarily be aware of this – or need to be – there are no accidents in “More Than A Feeling” — every element is as deliberate and calculated as a scientific formula. Very, very rarely has such cold precision been so effectively utilized in the service of such a truly emotionally suggestive result. Every level is full of precise intent (even a drum roll, which signals the entry of the verse vocal, seems a little “hot” to the listener, but is clearly “intentional,” awakening the listener out of the slumber of the seductive arpeggio), and likewise, as the song moves from section to section (and there are a pile of them, subtly different but unified, all serving the emotional and structural grace of the larger piece without ever disrupting the flow), different guitars shift as needed, sluicing and gliding in and out without ever breaking the flow of the song or making the listener conscious of all the work going on. As we move into the chorus (brilliantly set up by a melodically inventive pre-chorus, where a guitar sings a brilliant lead melody — and although there’s a lot of single-line guitar work in the song, there’s no soloing, every guitar ‘run’ is a part, not a solo), something extraordinary happens…

In the history of “heavy” rock, there are many stunning, staggering, shattering rhythm guitar sounds – It’s hard to beat the signature tear and roar of Leslie West, Fu Manchu’s Scott Hill, and Johnny Ramone – but very little in the history of riff-roar tops the sound that Tom Scholz achieves in the four-chord slurring, skipping chop on “More Than A Feeling.” It beautifully combines the heavy with the fleet, the instantly attention-grabbing with the non-disturbing.

And unlike the aforementioned West, Ramone, and Hill (not to mention Iommi or Townshend), it’s a synthetic sound, and immediately identifiable as such, built of multiple guitars, expertly tweaked boxes and amps, and perfectly calibrated tape. This is a signal moment in the history of guitar rock; although “processed” guitar sounds had been used extensively in music, rarely had they been applied to the fat, thick, sexy riffs of hard rock; that moment ends with “More Than a Feeling.” And although this discovery would be greatly, horrifically abused in the future, for one shining moment, it is utterly perfect. Like a thousand cups of sweet cream poured over a Golem-esque Dave Davies wandering through Stonehenge, the primary riff of “More Than A Feeling” crunches without aching, shakes without breaking, whirrs without screeching; it is, in a word, the rarest combination of a perfect riff with a perfect sound with a perfect song. This so rarely happens; for instance, “You Really Got Me” may be one of the fundamental riffs of all time, but it’s difficult to listen to it without wanting the guitar to sound just a tiny bit, oh, wider; “Mississippi Queen” starts out as the best goddamn thing you ever heard, but kind of meanders through the un-mapped woods of a less than perfect song; it’s hard to top the “Sweet Jane” riff, but the “official” released version of the track is flawed, both in mix and composition; and so on and so on. The riff to “More Than a Feeling,” the sound of the multiple guitars that build it, and the song it sits in are, well, perfect. One would have to look forward to Roth-era Van Halen to find a comparable mix of riff, recording, composition, and personality.

Where Was I?

Lest we get too hung up on the riff – and it is phenomenally easy too – the rest of “MTAF” falls together with equal genius and precision, achieving the ultimate thing a pop or rock recording can do: make the listener feel enraptured by the story and the texture while inserting enough changes and “surprises” to keep the listener alert. This lasts until the very end of the song; while the piece is fading out, the bass does an octave drop for the first and only time, and you know that this was done just to state “You thought you had heard everything, right?”

And all of it is an extraordinary product of Artisanal Recording. Tracks like “Dear Prudence” or “Getting Better” by the Beatles, or “Knights in White Satin” by the Moody Blues or “Wish You Were Here” by Pink Floyd are just extraordinary recordings of extraordinary performances of extraordinary arrangements of extraordinary songs played by extraordinary bands; “More Than A Feeling” is a piece where the studio (by which I mean the whole apparatus – console, tape machines, outboard gear, EQ’s, etcetera) is an extra musician, and that musician is expertly, precisely directed by very, very skillful hands who (as Einstein said about God) do not play dice. There is zero dice playing on “More Than A Feeling,” and what makes all this so much more remarkable, it is accomplished entirely in the era before there was computer automation of recording boards, much less computerized mixing or recording. “MORE THAN A FEELING” IS THE PRODUCT OF HUMAN HANDS CREATING ART, WORKING SO CAREFULLY AND DELIBERATELY THAT THE PRODUCT OF THE HANDS AND TOOLS CAN AND MUST BE SEEN AT THE LEVEL WHICH WE WOULD APPRECIATE THE WORK OF THE MOST SKILLED ARTISAN.

(And that’s even without discussing the amazing vocal performance, achieved entirely without auto tuning or the vari-speeding that, for instance, was used so widely by Led Zeppelin. It is genuinely heartbreaking to think that no one will ever sing like that again, like Brad Delp or Freddy Mercury or Steve Marriott; auto-tuning, which, when expertly used, is undetectable, makes the art of pure rock singing extinct).

And it’s all gone, gone, gone. The day of Artisanal Recording is literally as dead as analog television, the rotary dial phone, or the typewriter ribbon. Never again will hands (or a series of hands) scramble in frenzied coordination across a mixing desk to achieve precise, seamless results; I am old enough, thankfully or not, to remember being part of recording mixes where you would have six or eight hands on a single mixing desk, moving in excited and exact calibration, a performance in and of itself.

Now, these days computers do it all. And I am NOT a Luddite; in fact, as a producer and musician, I probably PREFER that. Never again do you need to go with a very, very slightly botched mix because you just can’t run that whole complicated mix one more time and fix that tiny little mistake four minutes into the song; likewise, computer recording programs encourage the musician to create wonderful and subtle events for the briefest moments or towards the most delicate end. So, personally, I am actually all for the computer recording era, I just honor the extraordinary artisans who would do it all with their hands.

And, as it happens, there are plenty of luddites out there who will tell you “Oh, ya gotta use tape, man.” But unfortunately, the kind of musicians who do insist on using tape are not the kind of musicians who are building Brunelleschi’s Dome, like Tom Scholz did with Boston, or Bjorn and Benny did with Abba, or Roy Thomas Baker and Queen did with “Bohemian Rhapsody” and a pile of others. The musicians still using tape are, without exception, trumpeting some kind of useless primitive theory, and as I stated much earlier in this piece, I have found I can make garbage sound more like garbage with computers.

There will probably come a time, in the relatively near future, where some filmmakers with a small digital camera, a green screen, and a computer can make something absolutely as mysterious and beautiful as the extraordinary chiaroscuro of the sewer chase scene in The Third Man or the Bruegel-esque dreamscapes of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. That moment has already happened in music, and the age of the Artisanal Recording is over. Next time you hear “More Than A Feeling,” remember what the grace, coordination, wisdom, time and art it once took to make a seamless pop recording, and honor it.