In 1973, I was unarguably a child, arguably pre-sexual, and extraordinarily curious about the world around me. I was also constantly aware that I was being conned. I knew that the people I saw on television were strangers; not just strangers to my way of life (full of the usual oppressions, limitations, disenfranchisements, and handicaps of pre-pubescence), but also strangers to reality: these characters, these Bradys, these Partridges, these summertime replacement sketch comics, they were caricatures that reflected reality no more – and often far less – than cartoon characters did.

Very few eleven year olds are free. Not only are they almost completely dependent on family and parents, but their worldview is defined by available and accessible media (and their generational peers vomiting up the same). At that age, in any era (not just the rotary phone/terrestrial television world of the early 1970s), even in this era, young people are a grotesque and addlepated mofungo of their environmental influences; we don’t know who we are, but we try to form an image of ourselves based on the slivers and shards of a thousand funhouse mirrors the world throws all around us. In fact, virtually none of these mirrors reflect our actual selves in any functional or useful way. Each child is full of great depth, in many ways the same depth they will presume and assume as adults, yet we have to construct a world out of the largely one-dimensional residue of what adults presume to be our usefulness as consumers.

Very few eleven year olds are free. Not only are they almost completely dependent on family and parents, but their worldview is defined by available and accessible media (and their generational peers vomiting up the same). At that age, in any era (not just the rotary phone/terrestrial television world of the early 1970s), even in this era, young people are a grotesque and addlepated mofungo of their environmental influences; we don’t know who we are, but we try to form an image of ourselves based on the slivers and shards of a thousand funhouse mirrors the world throws all around us. In fact, virtually none of these mirrors reflect our actual selves in any functional or useful way. Each child is full of great depth, in many ways the same depth they will presume and assume as adults, yet we have to construct a world out of the largely one-dimensional residue of what adults presume to be our usefulness as consumers.

The list of the fears that shadowed my 11 year-old world was long and common: the end of the world; the mortality of my parents; the thick shadows of the bullies or the lock-jawed disapproval of the teachers; the terror caused by lifts home from Hebrew school that never came; not to mention the foreshadow of sex, mysterious almost to the point of being otherworldly. Honestly, not a single minute of any television show spoke to any of these issues, yet television was our world, our refuge from screaming families and fall-out drills and all the aforementioned everyday terrors.

I was aware, when I watched anything except for the news (Vietnam! Spiro Agnew! John Lindsay! Mario Biaggi! The Columbo Family! Joan Whitney Payson! Aristotle Onassis!) that I was not watching reality; I was not watching anything that told me about who I was and who I might become.

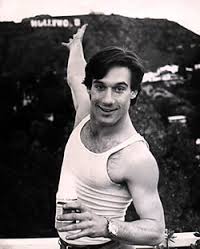

Into this world, this world of fear and fakery, stepped Lance Loud.

He was light, he was beautiful, he was an angel, he was utterly unlike anyone I had seen on television (and I watched a lot of television, being lonely, strange, and chubby), the world to him seemed to be a suitor to be charmed with a flip of your hair and a sly comment. Even within the documentary format of the show that featured him, An American Family, he seemed hyper-real, like the birdsong heard for only eight seconds that is more beautiful than any recorded composition.

I immediately fell in love, even though I knew nothing yet of sexual desire, much less the mechanics of homosexuality. I fell in love with his joy, his lithe, rubbery spirit, this person who seemed free and real and so strange yet so utterly familiar; he was the dreams I had not yet had (but only suspected); and what was most important about Lance Loud wasn’t that he was the first openly gay person on television (more on that in a moment), but he was the first utterly real person on television, the first person who reflected us at our most sensitive, at our most truly silly, at our most casual and cavalier and intense and introspective, at our most flippant or flirtatious; he, alone of anyone on the Empire of Television, seemed to understand that we might dance in front of a mirror and be someone we never could be (or precisely the person we would become!), he alone seemed to understand that while riding a bike down a suburban street we might pretend, for 48 seconds, to be the king of an empire that had the same name as our street. In other words, he was the first person on television with an interior life.

I immediately fell in love, even though I knew nothing yet of sexual desire, much less the mechanics of homosexuality. I fell in love with his joy, his lithe, rubbery spirit, this person who seemed free and real and so strange yet so utterly familiar; he was the dreams I had not yet had (but only suspected); and what was most important about Lance Loud wasn’t that he was the first openly gay person on television (more on that in a moment), but he was the first utterly real person on television, the first person who reflected us at our most sensitive, at our most truly silly, at our most casual and cavalier and intense and introspective, at our most flippant or flirtatious; he, alone of anyone on the Empire of Television, seemed to understand that we might dance in front of a mirror and be someone we never could be (or precisely the person we would become!), he alone seemed to understand that while riding a bike down a suburban street we might pretend, for 48 seconds, to be the king of an empire that had the same name as our street. In other words, he was the first person on television with an interior life.

When I looked at Bobby Brady, I saw no interior life; and when we are children, when our lives are full of the most beautiful secrets (mostly the secrets of our strangeness, for every child is strange, for one minute an hour, or one hour a day, or for one year of a life, until the strangeness is hyper-normalized out of them!), when our lives are full of the belief that the world is full of infinite possibilities and infinite miracles and a million ghosts and a million stars, we are ALL interior life; and Lance Loud, long and grinning with lips that split the screen, clearly not only had an interior life, his interior life looked like ours, and he wore it on the outside.

Now, that’s just my personal perspective. In a more universal sense, let me state this clearly: Lance Loud was the first announced gay man on American television. Do you know how fucking huge that was? He was Jackie Robinson, he was Louis Armstrong, he was Neil Armstrong, he was Chaplin, he was Crosby, he was that important. In our revisionist perspective, we see the world of the 1950s and ‘60s as being full of visible gays: but not only were these gays unannounced, they were often broad caricatures, easily dismissed, objects of fun or ridicule. Paul Lynde, Liberace, Truman Capote, these gentlemen were caricatures, and deliberately ridiculous, and the source of ridicule, and if they waved any flag, it was the flag that their sexual predilection was like the name of a Hebrew God, not to be spoken aloud, and thereby easily denied and easily mocked.

But here was Lance Loud: Lance Loud might have been gay, but he was also our brothers, our sons, our neighbors, our schoolmates; he was a part of us (and if we were deeply a fantasist, like so many of us were, he was most of us, he was the best part of us!), he was gay, he was on television, he was real, he was not a figure of fun or ridicule, he was gay and the on television and more realistic than any boy next door; which is all to say that Lance Loud wasn’t just the first gay on television, as deeply important, indeed historic, as that is; he was also the first real boy on television.

He was complicated, shaded, confused, arrogant, funny, tragic, he was everything we suspected a sensitive soul such as ourselves might be, but we had never seen one before outside the shadows of our own hopes!

He also carved the idea, somewhere in the willing, supple, and soft balsa-wood of my brain, that our fantasy self, our fantasy I, so private, so lonely, could one day be a we, we might meet others like him, like us, we might meet Morrissey or Michael Stipe or Dean Johnston, he instilled the idea that we were not overly sensitive, but appropriately sensitive; Not overly artistic, but appropriately artistic; Not overly bookish, but appropriately bookish; Not overly fey, but utterly beautiful in our own true boy skin.

Lance Loud was the first true boy on the sun, which is to say, he was real, he reflected a thousand and eight hopes and flaws and realities and shades of masculinity, and the sun was the television, beaming his brightness all over America.