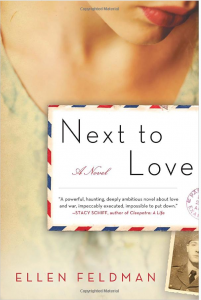

The title of Ellen Feldman’s novel is ascribed to Eric Partridge, the British lexicographer, who, as a young recruit, wrote of “war, which, next to love, has most captured the world’s imagination.” In the novel, Babe Huggins works for Western Union, snipping lines of telegram tape as they chug from the receiver, then gluing them in order onto light slips of paper before handing them off for delivery. The book opens on the harrowing day in 1944 when 16 telegrams from the War Department, each announcing a casualty, arrive in her small Western Massachusetts town. Since her own husband, as well as the young husbands of her two best friends Grace and Millie, are fighting in Europe, Babe feels a clutch of fear and a burst of relief as each name of a dead soldier comes across the wire.

“Next to Love” follows the three young women as they and their husbands grow up into a world at war. And while the book is about death, but it’s equally about sex:

Babe does not take long to learn the dirty little secret of war. It is about death. Everyone knows that. But it is also about sex. The two march off to battle in lockstep.

Her discovery is not original. Eros and Thanatos, she will read later . . . But Freud did not have her firsthand experience.

All three of the young women experience sex and marriage (sometimes in that order); all three are war brides. You will have guessed that at least one learns she is widowed on that day in 1944, but the book is not all about that. It’s about the effect of the war on these young women, and the children they will have, and the fathers of those children. And the burdens that the men who do return bring home with them.

In some ways, the war was liberating for women. In “Next to Love,” Babe leaves her Massachusetts home, following her husband Claude to training camp. She returns home when he is shipped overseas. She gets the job at Western Union because nearly all the men are away, but learns as the war winds down that she must give up her job once it’s over – the returning men will need all the jobs. It seems hard to explain now, the fact that only a few women stayed in the workforce in 1945, the rest easily giving up their jobs to the men.

All the same, it’s refreshing to read a book about the home front during the war, one that deals with the hardships then and in the aftermath: the secrets, the repression, the relationship of stepfathers to children who never got a chance to meet their biological dads. And this is a well-written one. Do you agree? Let us know in the comments.

Have a book you want me to know about? Email me at asbowie@gmail.com. I also blog about metrics for people who hate numbers here.