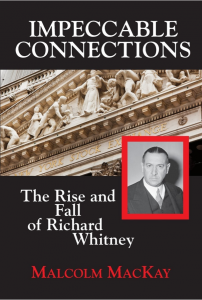

Richard Whitney had everything: a seat on the Stock Exchange (he was its president for five years – the youngest president ever elected), a devoted wife, a townhouse on East 73rd Street in New York City and an estate in the horse country of Far Hills, New Jersey. He came of old WASP stock, went to Harvard where he was elected a member of the exclusive Porcellian Club, and rubbed shoulders with what was as close to an aristocracy as the United States has ever produced. And yet he went to prison for embezzlement. Who was he, and why did he steal? Brooklyn Heights resident Malcolm MacKay explores the man and his acts in this slim biography.

And what an interesting story it is. Whitney’s family did not come over with the Mayflower or even with John Winthrop. The earliest Whitney, a tailor, arrived fairly early, however, in 1635, and the family stayed in Watertown, MA, for several generations. Some later descendants moved to nearby Beverly, and one of those, Richard Whitney’s uncle Edward, became a partner of J.P. Morgan in 1900. Richard Whitney himself was born in 1888. He attended Groton before going on to Harvard. His older brother, George, followed their Uncle Edward into J.P. Morgan, eventually becoming head of the firm. It was Uncle Edward who loaned Richard, aged 23, the money to buy his seat on the Stock Exchange.

The early years of the 20th century were a heady time to be a member of the Exchange, and Richard had a particularly easy time of it: his most important task was to broker Morgan’s bond trades. That work provided Whitney a steady income. But, MacKay points out, Whitney never did much to develop any business beyond that. Whitney did a great deal else, including serving as Master of the Hunt at a fox hunting club in New Jersey. In MacKay’s description, Morgan and his partners ran the Exchange as another private club, and argued vociferously to the government that they could self-regulate. That approach worked, for a while: in fact Whitney, working on buy orders from Morgan, was the public face of the bankers’ successful attempt to arrest the Black Thursday panic.

MacKay is at his very best describing the quirks and foibles of America’s upper classes. Endicott Peabody, Whitney’s old headmaster at Groton, “would visit old boys, including Roosevelt in the White House, and he made no exception for Whitney in Sing Sing.” Richard Whitney’s brother, George, and other Morgan partners, worked until the end to help Whitney, and, in a holdover from the days when the market really was their club, chose not to report him to the authorities. To his credit, Whitney’s brother George “over time — made good on all the bad loans and embezzled funds.” And once there was no other way out, Richard himself behaved impeccably, pleading guilty and serving his time, with time off for good behavior. “No whining. No pointing at others. No plea bargaining. The gentleman just happens to be an embezzler.” MacKay includes an extraordinary picture of Whitney entering Sing Sing with his head high. He’s handcuffed to another prisoner, who is hiding his face, something MacKay tells us “Whitney would never do.”

The sense of betrayal was overwhelming, and most of Whitney’s friends dropped him. Though described as a snob throughout his life, Whitney managed well in prison (where he was treated with some deference). How would you have punished him? Let us know in the comments.

Have a book you want me to know about? Email me at asbowie@gmail.com. You can read my other blog on my website, asbowie.net.