I don’t know about you, but I generally think of the Winter Olympics as the Second Darrin of Olympic Games…but boy, the airborne, ice dancin’ excitement of the Sochi Snowthletes may have me changing my mind about that! Yessir, ol’ Mr. Remarkable had a grand old time sittin’ back in his Craftmatic, a Rob Roy in one hand (don’t be stingy with those bitters, barkeep!) and a Lucky Strike in the other, watching winter’s most talented boys and gals go for the gold.

But did you know that the Winter Olympics were once almost in Brooklyn!

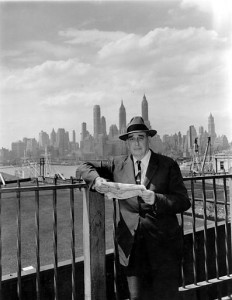

The story starts in 1936 with Stephen W. McKeever, the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. One day while watching a ball game, he and his pal Robert Moses (yes, the master builder – try sayin’ those two words three times fast!) were jawin’ about the pomp and spectacle of the recently concluded Olympic Games in Munich. They agreed that the krauts could sure put on a show, but they thought they could do better! So McKeever and Moses decided to join forces and bring an Olympics to Brooklyn!

The first thing they needed to do, of course, was put together a good proposal, and pitch it to the International Olympic Committee, who were then headquartered in Lausanne, Switzerland. Now, Moses and McKeever cleverly thought that getting the winter games would be easier than getting the summer ones! The Winter Olympics were only a few years old at that point (they had started in 1924), and they weren’t the big deal they were to later become (in fact, the first Winter Games in the U.S., in 1932 in Lake Placid, had been a decidedly tepid affair – only fourteen events in four sports were staged, and many of the world’s greatest winter athletes were no-shows because they didn’t want to spend the money to come over from Europe!). In fact, this was one of the things Moses and McKeever wanted to change, and oh boy oh boy, they had big plans.

In January of 1937, McKeever, Moses, and famed architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, arrived in the land o’ banks and chocolate (that would be Switzerland! Ha!) to try to convince the IOC to award the 1944 Winter Olympics to Brooklyn! Here’s what McKeever, Moses, and Mies had in mind: They wanted to build an ARTIFICIAL MOUNTAIN in Prospect Park for all the downhill skiing and bobsleddy-type events; they wanted to convert Bed Stuy Armory into a state-of-the-art indoor arena to house hockey and skating; and they wanted to put a ROOF on McKeever’s own Ebbets Field, so they would have a site for a majestic opening and closing ceremonies befitting the grandeur of the games!

Boy, the ’44 Brooklyn Winter Olympics was sure gonna be a sight to behold!

Moses, of course, had long-term goals in mind: he hoped to make the Prospect Park mountain permanent and create an income generatin’ tourist attraction to bring skiing and hiking into the city (it would be called Mount Moses, of course); and he also wanted to keep the dome on Ebbets Field, to create a forward-looking monument to the future which he hoped would compliment his plans for the 1939 World’s Fair, then being built in Flushing Meadows’ Park.

Well, when the Moses and his pals presented their ambitious plans to the crusty old burghers at the IOC, the reaction was swift. Henri de Baillet-Latour, the Belgian head of the IOC, bluntly pronounced “C’est le travail de rêveurs et les Juifs, bien haut sur l’opium Hébreu” (“This is the work of dreamers and Jews, clearly high on Hebrew opium”); and with that one withering sentence, he dismissed Moses, McKeever, and Mies, and awarded the 1944 Winter Olympics to the city of Cortina d’Ambezzo, Italy.

Moses was never one to take defeat lightly. Angrily, he announced that he would start his own International athletic competition to compete with the Olympics; this would be called The World Congress of Athletic Progress, and he would hold it every two years, to be permanently housed in the new Brooklyn winter paradise Moses was planning on building. Now, McKeever thought that such an endeavor would surely bankrupt Moses, McKeever, the Dodgers, and the borough of Brooklyn, so he suggested to Moses that they all be good sports and accept that you win some, you lose some (a phrase first attributed, by the way, to the Roman Emperor Elagabulus; very shortly before his execution in 222 A.D. for his “unspeakably disgusting life”, ol’ King Gabby famously said “vincis, aliquam perdas”). Well, ol’ master builder Moses didn’t like that kind of conciliatory talk, and he attacked his former partner with a rather large decorative ashtray presented to him in 1935 by New York Governor Herbert Lehman. This incident was later hushed up, but there are some who believe the injuries Moses inflicted on McKeever contributed to his death in 1938, though that’s never been remotely proven.

But that’s another story, and Moses plowed ahead with his plans for his own personal Olympics. To help promote the idea, he enlisted some corporate sponsors, high-profile politicians, and contemporary celebrities for a radio telethon to both raise money for The World Congress of Athletic Progress and familiarize the public sector with the concept. So, on November 14, 1937 a telethon titled Champion Spark Plugs and Pepsodent, the Antiseptic Toothpaste Present Muscle, Pride, and Progress aired on the Mutual Broadcasting Network, beamed live for eleven hours from the Mutual studios at 1440 Broadway. It was quite an event! Hosted by Comedian Fred Allen and surrealist painter/celebrity Salvador Dali, the remarkable evening also featured performances by the Boswell Sisters, Orson Welles, Kay Kyser, Chester Lauck and Norris Goff of Lum and Abner, Ed Wynn, noted juvenile Eddie Cantor impersonator Larry “L’il Banjo Eyes” Kase, the Dandy Dixie Minstrels, and star athletes from the New York Giants (Moses had switched team allegiances after the rupture of his relationship with McKeever).

The telethon was a disaster. First of all, in order to emphasize the gravity of the event, Moses insisted that every reference in the script to the proposed inaugural games of The World Congress of Athletic Progress (slated at that time for February, 1942) include the date being written out in Roman Numerals. This detail wreaked havoc with all the talent on the show, who found themselves attempting to pronounce “MCMXLII” as a word! By the middle of the show, the considerable vocal talent had agreed upon a pronunciation of “Mick-Mix-ell” (as in “I’m Ray Corrigan, and Ernest Truex, Rosita Serrano and I want to tell you about The World Congress of Athletic Progress in February of Mick-Mix-ell”), and this infuriated Moses to such a degree that he physically attacked Ed Wynn’s wife and infant daughter. Secondly, less than a third of the way through the marathon broadcast, news broke of the Japanese victory at Shanghai (in the ongoing and tragic Second Japanese-Sino War), and Mutual continually broke into the broadcast to update news about the event.

Within days, the grand idea of The World Congress of Athletic Progress was dead. Moses licked his wounds, concentrated on the 1939 World’s Fair, had Rita Serrano deported to Nazi Germany, and went on to many great projects, but Prospect Park never got it’s mountain, Ebbets Field never got its’ roof, and the remarkable events of the global conflagration known as The Second World War preoccupied everyone’s minds for years to come.

There was an interesting fall-out from the event, however: Salvador Dali and Fred Allen formed an unlikely friendship, with amazing results! The artistic insouciance and conceptual savoir faire of the genius artist and the witty, fertile, and febrile mind of the great comedian combined to come up with one of era’s greatest inventions: the toy we came to know as The Slinky. But that’s another story. Let’s just say that Dali saw the tightly coiled spring as the only possible reaction to the ludicrousness of the Civil War that had just wracked his native Spain (he envisioned the toys being dropped in the tens of thousands over the war-wracked plains of Andalusia), whereas Allen saw the ultimate commercial potential of the strange and mischievous object.

Once again, no time for THE THREE DOT ROUND-UP! Boy, there’s a lot of gossip and news piling up! AND THAT’S WHY I LOVE LIVING IN BROOKLYN!

(The author’s opinions and grasp of reality are entirely his own)

Tim Sommer has been employed as a musician, record producer, DJ, VJ, and music industry executive of some little note. He is the author of the critically acclaimed I, Wellonmellon: The Dark World of the Women in the Films of Jerry Lewis, and he continues his efforts to get the New York Mets pitcher Al Jackson into the Hall of Fame.