When I was a child, I would dutifully clip the facsimile Declaration of Independence that appeared on the back page of the New York Times every July 4. It was one of my favorite traditions. I did this every year, from about ages 7 to 11.

I would hang the newsprint declaration on my bedroom wall and stare at it. I would carefully copy the signatures; I would parse the encyclopedia for the biographies of the famous men whose names were contained therein; I would consider the significance and gravity of this great document, this famous lodestone of our nation.

I would spend much of the day playing patriotic music, committing famous historical quotes to memory, listening to the musical 1776, and considering the great characters in the magical story it told.

I would spend much of the day playing patriotic music, committing famous historical quotes to memory, listening to the musical 1776, and considering the great characters in the magical story it told.

I was not so much interested in fireworks – the noise frightened me, and the libidinous spirit their ignition seemed to encourage somehow made me uncomfortable. Also, on July 4, 1969, my brother had been bitten rather gruesomely by a dog deranged by the noise. So this whole aspect of the holiday had no positive association for me.

Weirdly, this annual burst of patriotism was not limited to Independence Day itself. Somehow, the sweep and grandeur of the Independence legend seemed to affect my overall personality and worldview. In fact, my fascination with the bewigged formation of the country, the great traditions and myths of Revolution and victory, and the traditional songs and stirring Broadway melodies inspired by America’s birth soon became a dominant aspect of my pre-teen personality (and a somewhat lonely one it was, too, no surprise there).

It was almost like the sweep of our country’s history became a myth full of giants, perfect to replace the dominant myth that occupies the young, the story of the dinosaur.

In fact, for all intents and purposes, I became a little neo-con. I was so fascinated with the story of the country that I presumed I must love the country, too. Being a wee-right winger also had the added benefit of being a truly rebellious act, something that set me apart from and even offended my peers. As distasteful as my 10-year old point of view may have been, I now recognize that it was likely the first time in my life that I actively set out to define a consistent path that would set me apart from my peers, as opposed to seek to please them or conform to their perceived social norms .

At that young age, and in an era lacking the pluralism and media ubiquity of the later internet age, I was unable to distinguish my love of history from the love of the results of history. I had not yet learned to discriminate between the fascinating, colorfully drawn actors and their actions, and there was no room in my worldview for accurate interpretation of the gray, black, and blue dynamic and results of those actions. I was in the thrall of the archive, so I presumed I had to be in the thrall of the men who filled the archive.

I now know that the story of the United states is deeply troubled and often shameful; full of extraordinary nobility, invention, and determination, but also laced with wrongful wars and obscene classism, and thoroughly weighted down – very nearly to the point of self definition — by the astoundingly ugly scar of racism, which was enabled by the almost unthinkable sin of slavery and the nearly as egregious corruption and failure of reconstruction.

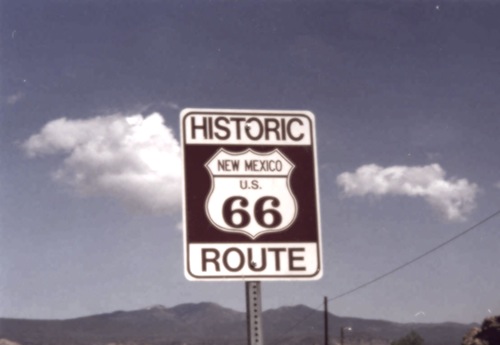

But the characters in the story are beautiful, their stories fascinating, it’s history rich and gripping, and I love it, love it, love it: From the rookeries of lower Manhattan’s 5 Points in the 19th Century to the manicured lawns of Asheville, North Carolina in the 21st; from the sepia shabbiness of old, beautiful Times Square to the grim, graceful heroes of the Confederacy eternally standing unsmiling watch over Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia; from the Stonehenge-like remains of the U.S.’s most beautiful monument, Route 66, to the bleached bungalows on Los Angeles beaches; from all of these places and all of the characters who people these places, and all the 880 million sacred and profane sites in this country and all their stories and storytellers and story listeners and story makers, America is the sum of our worst actions, our most fascinating stories, our most grotesque instincts and our most enlightened learning, and it is always, always bursting with the potential and the hope that the people who will make the stories of the future will be compassionate, generous, sympathetic, and kind.