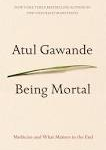

We are mortal: we’re born and, ultimately, we die. We resist the notion, we defy it, and eventually we succumb. What happens in the penultimate period, whether it’s weeks or months, is the topic of Atul Gawande’s very timely and useful new book “Being Mortal.”

We are mortal: we’re born and, ultimately, we die. We resist the notion, we defy it, and eventually we succumb. What happens in the penultimate period, whether it’s weeks or months, is the topic of Atul Gawande’s very timely and useful new book “Being Mortal.”

Gawande begins with the twentieth century, whose medical advances in the development of antibiotics, early cancer detection and improved treatments of a wide range of medical issues that would almost certainly have resulted in death only a few decades earlier resulted in many more people living into old age. In traditional societies, families took in the few elderly and treated them as founts of wisdom. Now there are many elderly, and as many baby boomers are learning, the elderly–their parents–are frequently frail in body or mind. Several other societal trends have coalesced: we live in independent rather than multi-generational households; the Internet has allowed huge areas of knowledge to be more widely available faster than an elderly person can impart it; and we regard aging to be a medical issue that can be treated. We live on our own; then, sometimes suddenly, we can’t. Too often, our elderly family relatives wind up in nursing homes, isolated and over-treated.

But old age isn’t necessarily something that can be treated. In earlier times, as people got sick, they declined steeply and died quickly. Old age, writes Gawande, is slow: it’s “the accumulated crumbling of one’s bodily systems while medicine carries out its maintenance measures and patch jobs.” It’s not clear why humans age-Gawande touches on two theories, one based on wear and tear, and the other in genetics-but we are embarrassed by aging, and, as a society, not coping well: we don’t want to face the fact that the falls and other byproducts of old age can be managed though not cured.

We value our independence and fear the coming frailty, Gawande writes. So we deny it, and although many of us will live through a dependent old age we fail to prepare for it. Eventually living at home becomes unsafe, yet the alternatives are unappealing. Children may be scattered across the whole country; their homes may be small, and they have careers and children to worry about. Companionship and health care are expensive; nursing homes, Gawande write, can be “frightening, desolate, even odious places to spend the last phase of one’s life.” They have become “a facsimile of home” where an elderly person is kept safe – but not stimulated, appreciated, or enjoyed.

What can we do to plan better? The medicalization of aging is a failed approach, and we are still searching for ways to ensure privacy and community even for people who are also dependent. Gawande points out that if we plan we can manage the decline without having to choose between neglect and institutionalization. Existing alternatives include family, though since so many households require two incomes, there are fewer daughters (and they are usually daughters) available to care for an aging parent. Good assisted living residences, which often have step ups to increased medical care centers, are emerging, but are expensive and not all operators are committed to providing all the services as the people who developed assisted living residences. Other options include making nursing homes better places,and Gawande devotes a chapter to ways to do so, including the use of birds, dogs and cats that give residents something to devote their lives to. Gawande offers no fixes here, though his vivid descriptions are thought-provoking.

But managing the decline is only part of the story Gawande tells. There comes a point at which we can no longer repair body parts and systems that are breaking down. Improving care and what Gawande calls maintenance at the end of life is Gawande’s deep interest. Gawande is not one to shy away from tough questions, and he addresses the issue of when to continue medical care and when to move to palliative care.

These days, swift catastrophic illness is the exception. For most people, death comes only after long medical struggle with an ultimately unstoppable condition . . . . In all such cases, death is certain, but the timing isn’t. So everyone struggles with this uncertainty — with how, and when, to accept that the battle is lost.

A move to hospice care is one possibility, but past policies have invested hospice with the notion that one is giving up. That, Gawande says, is a poor standard – there’s almost always something else to try. It’s important, he says, for doctors to have a substantive conversation about end of life care – a conversation in which it’s as important to listen and interpret as it is to speak and explain. The role of the doctor is to guide the patient – the consumer, after all – into making clear what he or she wants. These talks are difficult, and they end in death – but are worth it, Gawande tells us, because they improve quality of life in the last few weeks or months of life. (If you didn’t see it already, the New York Times published an essay adapted from the book describing the final weeks of one patient’s life.)

What are the questions? They are simple to ask with answers that are hard to hear. What is your understanding of the situation and its potential outcomes? What are your fears and hopes? What do you want, and what will you give up to get it? Medicine cannot always cure, and Gawande’s cogent argument is that it’s the person’s life, not the medicine, that’s important in the end.

Have a book you want me to know about? Email me at asbowie@gmail.com. I also blog about metrics at asbowie.blogspot.com