Marian Sutro, half French, half English, and raised in Geneva where her father was a diplomat, is living in London during the early part of the Second World War. Her parents are semi-retired, in Oxford, and her brother, a physicist, is working in London. Marian herself works in the Filter Room at Bletchley Park. When she is picked to train as an operative of the French Section of the Special Operations Executive she hesitates, but only briefly. During her training, she’s uncertain of her prospective role, though of course we know. One of the many interesting parts of reading this book is watching and responding to Marian as she figures it out.

Marian’s language skills are very good, and she thinks well on her feet. She has a tendency to disregard minor rules and to occasional impetuous behavior. Despite the insistence on secrecy she tells her brother Ned a bit of what she’s up to. And during her training course at a center in Northwest Scotland she “captures” a patrol of six soldiers while she and a friend are hiking on a rare day off. She’s not disciplined for this action, but not commended either – and when one of the six turns up again in her advanced training course, well, what she does is not entirely within the bounds of professional conduct.

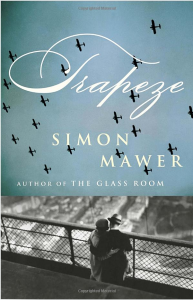

Despite her continuing disregard of the niceties, or perhaps because of her ability to improvise, Marian is sent into the field, parachuting into occupied France to be in place for unspecified actions. And she has a dual mission – the authorities want to persuade another physicist, Clément Pelletier, who may once have been in love with the teenaged Marian, to escape from France to work on the development of the atomic bomb. Clément is living in Paris, and Marian’s trip to Paris, as well as her various actions there, are the crucial scenes of the book.

They are also among the tautest scenes in the novel. Mawer is adept at slowing down the pace to inject tension. His description of occupied Paris – the miserable, hungry people, the pewter and tarnish of surfaces in what was the City of Light, the stress of responding with just the right mixture of servility and dignity to German soldiers – is spot on. Mawer’s portrayal of female sexuality and the war’s effect on it is both sensitive and absolutely credible. And his use of Marian’s names (she has various code names, cover names, and field names) is shrewd.

Is Marian too clever for her own good? What do you think of her final impetuous decision and its consequences, for Marian and for the novel? Let us know in the comments.

You can read my review of Mawer’s nove “The Glass Room” here. Have a book you want me to know about? Email me at asbowie@gmail.com. I also blog about metrics here.