Here is a stereo set, bought at Korvettes, overheated and smelling gently of warm plastic. It sits on a deep shelf in a teenager’s suburban bedroom.

It’s left on all night, and most of the day. It hums and buzzes and hollers and sighs as teeth are brushed in the morning, when homework is done in the afternoon, as diet sodas are sipped over impenetrable algebra in the evening, and when the lights go out after the news at night.

Mostly it plays LPs and 45s, largely British, full of accents and attitude and slurring power chords and sly observations, “Lucifer Sam” and “Well Respected Man,” “Honaloochie Boogie” and “Baba O’Riley.” Sometimes it plays cassettes of comedy shows taped off the TV.

When it’s not doing any of these things, the radio is on.

The signals, beamed from an Empire State Tower twenty miles to the west, arrive glowing and cozy, vibrating in the sweet, low/mid-range of the 1970s: highs ducked, the bass inviting and sensual, sluicing under and around you like a favorite sweater. Except to hear ballgames and scraps of news, it’s never set to the hissing sibilance of AM.

Even when the radio is top-loaded with songs offensive or uninspiring (to be useful only for triggering a Pavolovian nostalgia dribble two or three decades later), the frequency is still full of friends, which is to say, the voices of the DJ’s. They create the impression that they are speaking directly to you, sharing insights and discoveries (extreme, plain or passionate) with you and only with you.

And their names still shiver my heart to this day: Alison Steele, Meg Griffin, Pete Fornatele, Jane Hamburger, and most of all, Vin Scelsa.

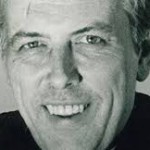

Vin Scelsa announced his retirement this week, after nearly half a century speaking from the heart to the hearts of music lovers – or just lovers of his company – in the New York City area. As I have stumbled across decades, states, and careers, I could say I have only infrequently thought of Scelsa – but that wouldn’t be true. I thought about him all the time (even if I didn’t keep up with his work, which I now regret).

Vin Scelsa announced his retirement this week, after nearly half a century speaking from the heart to the hearts of music lovers – or just lovers of his company – in the New York City area. As I have stumbled across decades, states, and careers, I could say I have only infrequently thought of Scelsa – but that wouldn’t be true. I thought about him all the time (even if I didn’t keep up with his work, which I now regret).

He was my friend. He was never far from my mind. Although I never met him, never even laid eyes on him, a lifetime ago he invited me into his world, which was open minded but discriminating; local in flavor but global in scope; optimistic but realistic; cynical but always inclusive of an ellipses which invited positive change; non-judgmental but with a healthy suggestion of the arched eyebrow of taste. In ways I can never quite detail, he helped shape me. As much as I might claim that I am a child of the golden age of open-minded/no-playlist FM radio (when mightily powerful New York stations would follow the Grateful Dead with Wreckless Eric, or the Good Rats with the Ramones), or the child of the Anglo-discoveries of Trouser Press magazine or the NME, or the child of the high ambition of shadowy and sepia-colored 1980 New York City, or the child of the great shabby and sexy god of 1980s college radio, perhaps the most significant midwife in my birth as a would-be Prince in the Kingdom of Outsiders was Vin Scelsa.

(The only other person on radio who ever reached me in quite the same way, who made me think they were a friend in the night speaking only to me, was Steve Somers, when he did the overnight for WFAN in the 1980s; but that’s another story, I suppose.)

I am delighted that this is not an obituary, but just a few words to honor a great man who contributed enormously to shaping my own strange and opinionated heart and mind, and the hearts and minds of thousands others, too. Today, we are generation (and more) past those school nights I spent in the winter dark and the spring gloaming scanning his weighty pauses for meaning; and I find that the music he played is not fully recalled, and that doesn’t really matter. Instead, I celebrate that I found — in his words, his joy, his doubts, and in his hope-fueled cynicism — an affirmation of the user-friendly idiosyncratic. Vin Scelsa was a coach compelling me to be myself and directing me to find the power of art and individuality in rock’n’roll.

Every time over the last forty years I have grasped for the peace-guns of music to reach someone’s soul, every time I have recognized that a few bars of music and a couple of guttural shrieks contain the ore of revelation, release, and revolution, anytime I have tried to make sense of a personal worldview that encompasses Boston and Wire, Rush and Rudimentary Peni, I am echoing the imprint of Vin Scelsa.

I have long believed that punk rock had only one (broad, all-encompassing, and all-loving) definition: To be open minded, to not fear the obvious, and to not fear the extreme (the extremely simple, the extremely quiet, the extremely loud, the extremely original).

I recognize, looking back forty years, that I have Vinnie Scelsa to thank for that.

Thank you so much, Vin Scelsa.